Just because children’s books are shorter than adult fiction, doesn’t mean they’re easier to write!

There are many things to consider when writing children’s books, from your target age group to readability, plot, characters, illustrations, and more.

In this article, we will focus on how to write a children’s book. We’ve got eleven steps to write a great children’s book, plus three top tips and a template to get you started.

I Want to Write a Children’s Book—Where Do I Start?

The key to creating a story that sells is coming up with an original idea. People will not buy a book that sounds like five other stories they’ve already read. If your idea is similar to something that’s been done before, think about how you can put your own unique spin on it.

This is true even for kids’ books. Your story and illustrations should stand out and provide a fresh experience for readers.

Many great ideas are born out of providing solutions to problems. What problem or problems are near and dear to you or people you know (especially children)? Could you write a book about that problem and how it was solved?

It’s important to choose a topic that interests you. You’ll be working on your children’s book for however long it takes to polish it. If you choose something you are interested in, you’ll be more likely to see it through to the end.

So, go ahead and brainstorm. The more ideas you come up with, the greater the chance you will find one you love. And that means the kids you are writing for will really love it too!

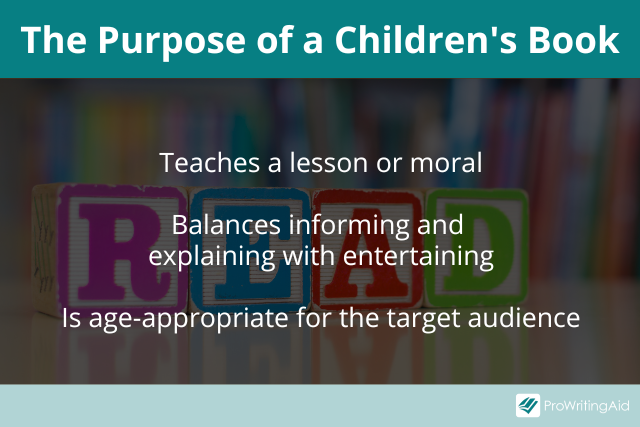

What Makes a Good Children’s Book?

Great children’s books appeal to both young readers and adult readers. But how do you write a children’s book that does this?

First, a great children’s book will teach children something, even if it’s a fiction book. It may teach a moral lesson, like being kind to others. Or it may teach social-emotional skills like doing scary things or dealing with bullies.

But it should balance informing and explaining with entertaining. Kids (and their adults!) want to enjoy the book they’re reading.

Entertaining children’s books use humor, rhyme, alliteration, onomatopoeia, or any other number of literary devices. They also have engaging illustrations that match the tone of the book.

Decide Who Your Target Reader Is

The first step in writing your children’s book is to choose your reader. Children’s books encompass a wide variety, from board books all the way to young adult books. If you know what type of book you’d like to write, then it’s important to make sure you’re aware of the ages of the children you’re writing for.

Each type of children’s book is geared toward kids of a certain age. Here’s a quick summary of the types of children’s books and the ages they’re appropriate for. We’ve also listed the word count expected for each of these children’s book genres.

Notice there is a bit of wiggle room. For example, if you’ve chosen a five-year-old protagonist for your story, you could write an early picture book, a chapter book, or anything in between.

Writing for a specific age group involves more than just the right word count, however. You must consider the reading level.

Age Ranges and Word Counts for Children’s Books

| Type of Book | Age Range |

Word Count |

|---|---|---|

| Board Books | 0–3 | 0–200 |

| Early Picture Books | 2–5 | 200–500 |

| Picture Books | 3–7 | 500–800 |

| Older Picture Books | 4–8 | 600–1,000 |

| Chapter Books | 5–10 | 3,000–10,000 |

| Middle Grade Books | 7–12 | 10,000–30,000 |

| Young Adult Books | 13–17 | 40,000–80,000 |

The content should also be appropriate for the age group. A children’s book about shapes and colors won’t make a great middle grade book. A story about starting middle school won’t appeal to toddlers.

The lines between middle grade books, young adult novels, and new adult fiction can get blurry. A 13-year-old may enjoy middle grade content contained within longer, harder books.

Many adult readers love young adult books, and many young adults prefer to read adult or new adult fiction. New adult is similar to young adult in format, tone, and pacing, but features characters over age 18 and often has explicit content.

Be specific in your marketing or when querying an agent about the age of your ideal reader. If you’re writing a young adult novel for older teens, you still need to consider reading level scores and appropriateness (kissing and fade-to-black can be okay, but explicit sex is not). However, you’ll use more traditional novel-writing advice to craft YA novels.

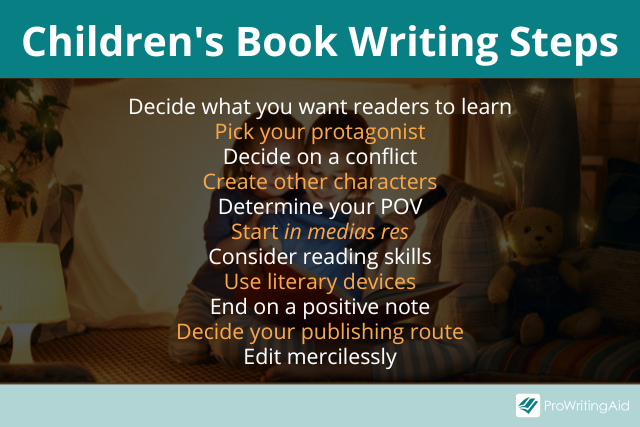

11 Steps on How to Write a Children’s Book

Once you’ve decided on your age group, it’s time to write. Here are eleven steps you can follow to help you learn how to write a children’s book.

1) Decide What You Want Young Readers to Learn

When writing children’s books, it’s a good idea to begin with the end in mind. Before you flesh out details like your characters and plot events, think about what you want readers to take away from your story.

Start with the main purpose of your story. Are you trying to inform? Inspire? Entertain? What feeling do you want your readers to come away with?

Then decide the primary lesson of your story. Don’t cram too many lessons into a children’s book. Pick the one takeaway you want kids to get, and keep it concise.

For a non-fiction book, your lesson might be something like, “Lions are big cats that live in Africa” or “Your lungs help you breathe.”

A fiction book might teach, “You are perfect the way you are,” or “Talk to a grownup when you’re scared.”

The takeaway will guide the characters you create and the story structure of your children’s book.

2) Pick Your Protagonist

Like any book, your children’s book needs a main character. There are a few things to keep in mind when selecting a protagonist for your story.

First, the protagonist should be relatable to your target age group. If you choose a human or human-esque character, they should be close to the age of your ideal reader.

Similarly, the protagonist needs to fit into the type of book you’re writing. Protagonists in picture books don’t need to be developed as much as ones in chapter books. A picture book will have one plot line, while chapter books will often have a couple of minor subplots.

If your protagonist’s age is vague, make them relatable in another way. Have them experience a common emotion: every kid knows what it feels like to be angry and sad. Or they could have relatable interests. In the book Rosa Loves Cars by Jessica Spanyol, we see Rosa playing with cars, which many kids love.

Consider diversity, as well. You can make a character that children of various ethnicities, races, genders, and family backgrounds can relate to.

When you write children’s books, you may need to expand your concept of what a character is. They can be animals or mythical creatures.

This is especially true for non-fiction books. The Baby University board books by Chris Ferrie and others do a great job of treating a concept like a protagonist. In Statistical Physics for Babies, the protagonist is a ball. We see the ball in different places, then we see more balls in different colors.

Children love balls, so using a ball to explain a concept like statistical physics and entropy is very effective.

Most importantly, have fun creating a protagonist. Embrace your inner child.

3) Decide on a Conflict

Once you have a protagonist, and you know the message or lesson of your story, you need a conflict.

The conflict is what your protagonist must experience to learn the story’s lesson. It’s the source of the plot for your story.

The plot is how your character deals with the primary conflict, so before you set up the events in the story, you need to have a solid grasp of the problem. Once you understand the story’s central conflict, writing the book becomes much easier.

4) Create Other Characters

Having other characters isn’t a necessity in books for very early readers, but for most picture books and chapter books, other characters flesh out the story.

An antagonist is a character that keeps your protagonist from achieving their goal. You may or may not have a true antagonist like you would in a young adult or adult novel. But you can include friends, sidekicks, parents, or interesting characters your protagonist meets along the way.

When you create characters, they should serve a purpose to the story. They might illustrate an idea, create conflict, or advance the plot. They can also highlight your protagonist’s character development.

For example, in Giraffes Can’t Dance by Giles Andreae and Guy Parker-Rees, most of the other characters are antagonists of Gerald the Giraffe. They tease him for dancing badly. But a cricket is the one who delivers the story’s lesson: anyone can dance, but you may need a different song.

However, in The Big Adventures of a Little Tree: Tree Finds Friendship by Nadja Springer and Tilia Rand-Bell, there are no antagonists. All the side characters are children who teach Tree what it means to have friends.

5) Determine Your Point-of-View

It’s important that your point-of-view fits the story.

For early readers, third-person limited or omniscient is often the best choice, especially if your protagonist isn’t human. This helps support babies’ and toddlers’ understanding of correct pronoun usage. Before age 2, most kids only use “I” and “it,” so first-person POV can be confusing.

If your story focuses heavily on emotions, first-person or third-person limited will help older children relate to the story.

Unlike most adult or young adult novels, some children’s books can use second-person POV. A great example is You Are My “I Love You” by Maryann K. Cusimano. The narrator is the parent and uses “you” frequently to refer to the bear main character and, by proxy, the child reader.

Think about what POV is best for your children’s book. You can also rewrite in a new POV if you decide it doesn’t work during editing.

6) Start In Medias Res

A children’s book still has the key story elements: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. But when you’re limited on word count and young readers don’t have much attention span, it’s important to get straight to the point.

This means that starting in medias res, or “in the middle of things,” is a great tool for children’s book writers.

Spend little time on setting the scene or backstory before you introduce the protagonist and their problem. For most picture books, this should happen on the first page. Aim for the first three pages in middle grade chapter books.

7) Consider Reading Skills

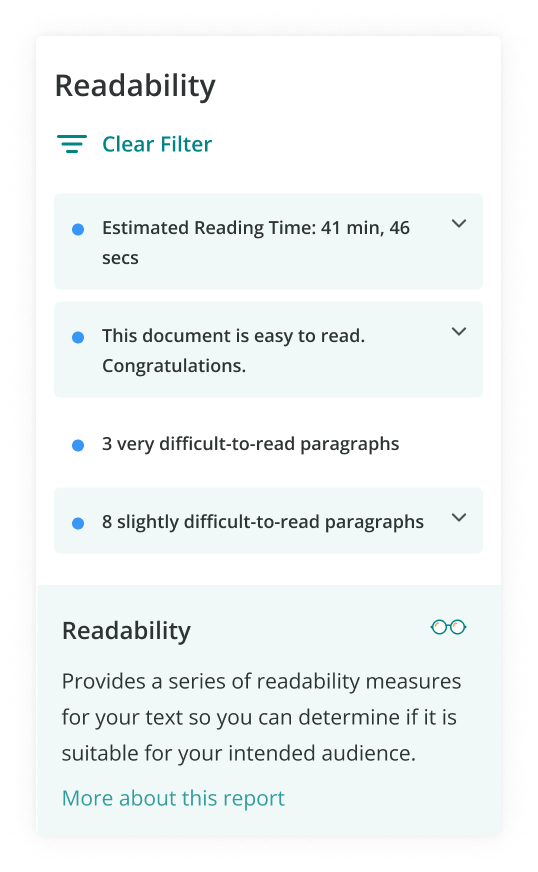

While all ages may love your story, writing children’s books requires a solid understanding of reading skills and readability scores.

Writing for a particular age range means you’re writing for the majority of readers in that group, not exceptional students who are developmentally above or below. The best way to ensure kids understand your book is to use a readability score.

Most readability scores are based on the U.S. public education system. The scores usually correspond to a grade level.

ProWritingAid can help ensure your writing is age appropriate. We primarily use the Flesch Reading Ease formula, which determines readability based on factors like sentence length and syllables per word. The higher the number, the easier it is to read.

Aim for a 90 to 100 on the Flesch Reading Ease for early readers, and aim for 80 to 90 for older children.

Other factors affect readability, too. Higher-level vocabulary, jargon, and complicated syntax also make your writing more difficult. ProWritingAid can offer you detailed suggestions to improve the readability of your work.

8) Use Literary Devices

Using literary devices like rhyme or alliteration isn’t just fun: it actually helps early readers learn!

Rhymes, alliteration, and assonance (repeated vowel sounds) help kids with phonemic awareness. This is the linguistic skill of understanding basic sounds in a language.

They also contribute to teaching rhythm in a language. The way we speak and write impacts tone and meaning. Rhythmic prose in a children’s book helps kids learn this feature of language.

You can also use other literary devices. Onomatopoeia (words that sound like their meanings) keeps young readers engaged.

Repetition also helps with reading comprehension. Click, Clack, Moo: Cows That Type by Doreen Cronin, and all its sequels, use repetitive onomatopoeia to help early readers understand the story.

You can also use imagery, especially in middle grade picture books and chapter books. This helps children learn description and draws them into the story.

9) End on a Positive Note

This one might be obvious, but when you’re writing a children’s book, the ending should be happy or uplifting.

Some stories naturally lend themselves to a happy ending. But if you’re writing about a sensitive topic, you might wonder how to write a children’s book that is happy.

Let’s say you’re writing about how to handle the death of a grandparent. This is a sad topic, but you don’t want to end with saying goodbye at the funeral.

Instead, you can show your protagonist remembering happy memories of their grandparent. The book can talk about ways to honor the grandparent’s memory, or how the character will always have their loved one in their heart.

10) Decide Your Publishing Route

Deciding whether to do independent publishing or traditional publishing for your children’s book will determine your next steps in the writing process.

If you decide to publish traditionally, you’ll need to query agents with your story. Publishing houses usually pick your illustrator for you. It will probably be someone in-house, so you won’t need to hire a professional illustrator. Of course, you can pitch your own illustrations, but the publisher may go a different route.

But if you’re publishing independently, every decision from book size to illustrator is up to you. We recommend talking with several professional illustrators to find out their experience. Also, look at their portfolios to see if they can match your vision.

While you have the possibility of making a lot more money with self-publishing, it’s a lot more work. You must do all marketing and sales yourself. Some children’s book reviewers will also not review self-published books.

You stand a greater chance of getting into libraries and bookstores if you’re traditionally published, and you can often get an advance on your royalties. But you will get lower rates on your sales and may lose some creative control of your story.

There’s no right or wrong option, but research both in greater detail to find out what the best choice is for you.

11) Edit Mercilessly

Editing a children’s book doesn’t just mean proofreading and improving your readability score. It means your story should undergo several rounds of revisions to be the best it can be.

Get feedback from other writers or professional editors. Pay attention to the flow of your story. Are the events in the story in a logical order? Is there extraneous detail you could omit?

Ask yourself if it will hold a young reader’s attention. Pay close attention to word counts and how many words are on each page.

3 Tips to Help You Write Children’s Books

1) Read Lots of Children’s Books

Good writers are good readers. The best way to learn how to write a children’s book is to read lots of them!

Reading stories meant for children will help you understand the best way to simplify concepts in ways that make sense to young readers. Don’t just read stories that are similar to your idea or fit your target audience. You’ll learn about different styles of writing if you broaden your horizons.

Read a variety of children’s books. Don’t just focus on classic children’s literature—pay special attention to reading a diverse range of authors.

Don’t worry that you’re stealing ideas. All art comes from inspiration, and writing a children’s book is no different. You’ll still be able to put a fresh spin on your unique idea.

2) Make Friends with a Librarian

You can just visit the children’s section of a library or bookstore to get a better understanding of kids’ books in general, and this is a great place to start.

But you will also want to see what books are like your idea. Maybe you want to see books that deal with similar topics or themes. You might want to look at a certain type of narrative structure.

Librarians can help you better than just about anyone. Tell the librarian about your story and ask for recommendations. This will save you time from doing market research by yourself. Librarians read hundreds of children’s books a year, and they know which books are popular with kids.

Many libraries have dedicated children’s librarians, and they have a wealth of knowledge about child development, age appropriate literature, and readability.

Librarians can also help you with research if you’re writing about a non-fiction topic, historical fiction, or anything else you may need to know.

3) Ask Kids What They Think

The best people to ask about your children’s book are kids. When you’ve finished a draft, find some kids to read your book to. If you aren’t a parent of your target age group, reach out to friends and family. You can also talk to teachers, librarians, or parents in your community.

Pictures help kids pay attention, so even if you aren’t an illustrator, you can use clip art or stock photos to make temporary illustrations.

Children are brutally honest, so be prepared for your harshest critics. If you are writing for an age that doesn’t talk much yet, see if your story holds their attention.

Template to Help You Plan Your Children’s Book

There’s no one right way to write a children’s book, and there’s a big difference between writing a board book and writing a chapter book.

This template is a starting point for your planning. It’s guided brainstorming, and you’ll develop your story as you write and edit.

A great way to plan your overall story is using this formula:

Somebody wanted but so then.

We can sum most stories up using this formula, so why not use it to plan a story?

Let’s break it down. Somebody is your protagonist. They want something. This is your character’s goal.

But something stands in their way. This is the main conflict of your children’s book.

So your protagonist must do something to deal with the conflict. Then something will happen based on their actions. This is the resolution of your story.

Now, let’s look at a more detailed template to flesh out this story. You may have more or fewer events in your story than this template has.

- Introduction: Who is your protagonist and what do they want?

- Conflict: Why can’t they get what they want?

- Obstacle 1

- Obstacle 2

- Obstacle 3

- Climax: How does your protagonist get what they want?

- Resolution: What have your characters learned?

You can spend however much time you need on each step. If you write a basic board book using this template, you will have a minimum of seven pages.

Conclusion on How to Write a Children’s Book

In summary, if you want to know how to write a children’s book, you need to read lots of books, know your target audience, have a relatable main character, and have an uplifting lesson or message.

Writing a children’s book should be fun. Embrace the silly side of the writing process. Give yourself permission to make mistakes.

You were once a child who loved stories, so it’s time to reconnect with your younger self.

(This is an update to an earlier article by Michelle Cornish.)